On any given day, we take anywhere from 17,000-30,000 breaths. Much like blinking or swallowing, breathing is not something we have to think about. If you are healthy, you likely view breathing as a natural and involuntary activity. But have you ever given thought to the quality of your breathing? Conscious attention to breathing can provide insight into both your physical and emotional states.

The role of respiration in overall health should be of particular interest to physical therapists. As clinicians who pride ourselves on a whole-body approach, it is our responsibility to consider the role of breathing in physical therapy. After all, breathing is the basis for everything we do.

Why should physical therapists worry about breathing?

Physical therapists are movement experts. Therefore, we should account for every factor that can affect movement. Breathing is the fuel for movement, but how often do we consider the influence of breathing on our patients or include breathing in physical therapy treatments?

In our stressful and fast-paced society, many people are susceptible to developing breathing dysfunctions. These dysfunctions can feed into the functional impairments we see in the PT clinic. Breathing pattern disorders may contribute to musculoskeletal conditions by impairing motor control and compromising trunk stability.

Many athletes and patients display dysfunctional breathing patterns, limiting performance and increasing vulnerability to injury. If we fail to address these dysfunctions in rehab, then we are doing our patients a disservice.

Mechanics of respiration

Let's briefly review the mechanics of respiration. Some of us may need a refresher - especially if it's been a while since you sat in a cardiopulmonary class.

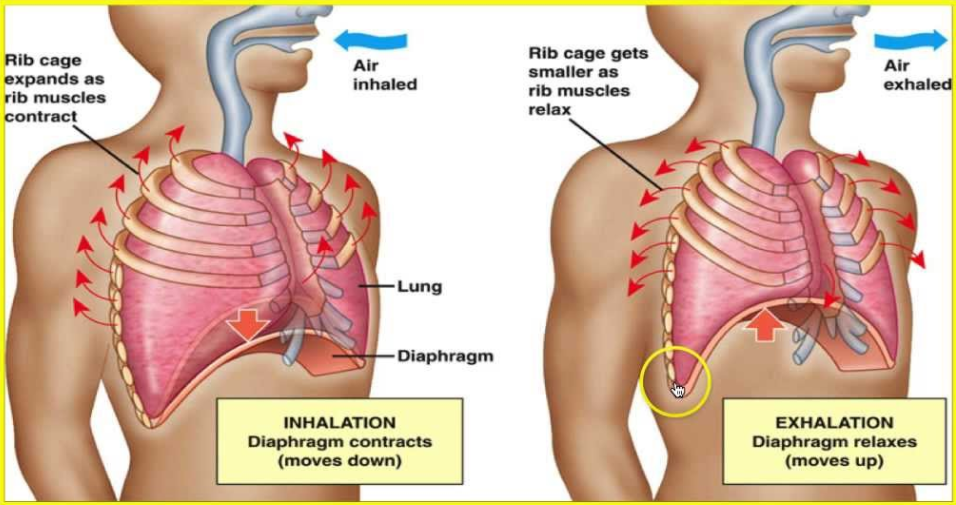

Inhalation, also known as inspiration, is an active process during which air enters the lungs. The diaphragm contracts and flattens and the ribs move upwards and outwards. As the dome of the diaphragm lowers, the overall size of the thoracic cavity increases. The volume of the pleural cavity increases as well. This expansion of the lungs is associated with a fall in intrapleural pressure.

Exhalation, also known as expiration, is typically a passive process, during which no muscular contractions are needed. At the end of inspiration, the respiratory muscles will relax and the chest wall and lungs elastically recoil. The dome of the diaphragm moves superiorly and the ribs depress. This results in a decrease in the volume of the thoracic cavity and a decrease in lung volume. This change in volume is associated with an increase in intrapleural pressure.

While expiration is primarily a passive process, it does become active during forceful breathing. For example, expiration is active when playing a wind instrument or during exercise. During forced expiration, the anterior abdominal muscles and internal intercostals contract, increasing the pressure in the abdominal wall and thorax.

Breathing and the nervous system

The nervous system and the musculoskeletal system work in tandem to create movement. If we have dysfunction with one system, it may manifest in the other system. Therefore, respiratory dysfunction in the nervous system may present as a musculoskeletal problem.

The control of breathing is balanced between the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system (somatic nervous system and autonomic nervous system). The autonomic division of the peripheral nervous system is of particular interest to us here. The autonomic nervous system is divided into the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system, and the enteric nervous system. Here, we will focus on the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system.

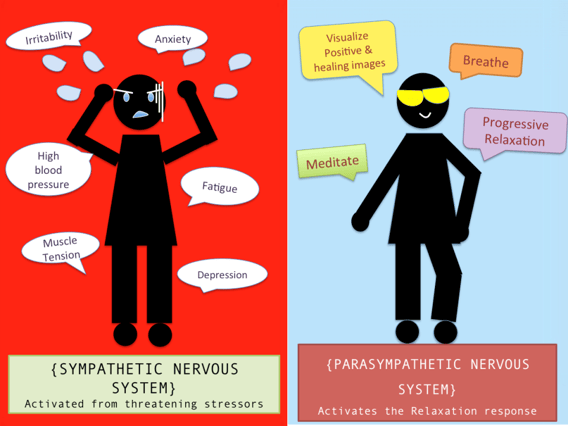

When we experience emotions, such as pain, fear, or stress, our sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems respond by adjusting blood pressure and heart rate (among other variables). Generally speaking, parasympathetic activity is associated with a relaxation response, and sympathetic activity is associated with a heightened response.

A slow diaphragmatic breath with prolonged exhalation will increase parasympathetic activity and result in relaxation. On the other hand, rapid chest breathing with prolonged inhalation will increase sympathetic activity and result in a stress response.

When we operate mainly through the sympathetic nervous system, we are living in a state of heightened arousal. This state is known as up-regulation. Up-regulation negatively alters our breathing patterns and changes the respiratory muscles we recruit for breathing. These changes can alter motor control patterns and result in musculoskeletal pain. Therefore, we should be assessing and treating breathing in physical therapy.

Dual role of the diaphragm

In early development, the diaphragm acts primarily as a respiratory muscle. However, at 6 months, the diaphragm takes on a dual role as a respiratory muscle and postural muscle. Both of these roles must be intact in order to achieve lumbopelvic stability and optimal movement patterns.

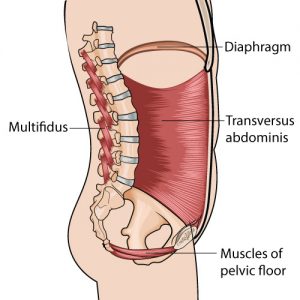

The diaphragm initiates core stability through its influence on intra-abdominal pressure. It works with the transverse abdominis, multifidus, and pelvic floor muscles to provide support to the spine. Proper diaphragmatic function not only allows us to breathe but also provides us with the postural stability that is required for complex movements.

When breathing demands increase, there is competition between the two roles of the diaphragm. Breathing will always win this competition (after all, we need it to live). As a result, the diaphragm's contribution to postural stability declines.

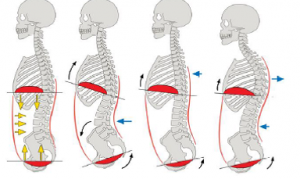

When individuals exhibit breathing pattern dysfunction, meaning they cannot diaphragmatically breathe or they are too dependent on accessory respiratory muscles, their bodies become hyper-focused on the demands of breathing. They will overuse other respiratory muscles and the diaphragm will be unable to perform its stabilizing role. Consequently, posture and movement patterns will suffer.

As physical therapists, we must remember that the diaphragm is a muscle. It is critical that we involve breathing in physical therapy treatments - we have to train the diaphragm too!

In many adults, we see breathing move away from the stomach and higher into the chest. These individuals are not taking full advantage of the diaphragm. The longer they under-recruit this breathing muscle, the harder it is to normalize breathing patterns and the more likely they are to develop musculoskeletal issues.

Breathing influences lower back pain

We have all used stabilization exercises to treat individuals with low back pain. While many of our patients improve with physical therapy, they too frequently experience recurrences of back pain, driving them back to physical therapy or onto pain medications.

Several studies have demonstrated the role of respiration on postural stability. In one such study, individuals with low back pain were compared to pain-free subjects during an active straight leg raise, an exercise that requires core control. Real-time ultrasound was used to examine the activity of the diaphragm and the pelvic floor. The subjects with low back pain demonstrated an increase in respiratory rate, a greater descent of the pelvic floor, and decreased diaphragmatic excursion compared to their pain-free counterparts.

These results indicate that subjects with low back pain had to work harder to breathe during a core control activity, but they used their diaphragm less. As a result, they likely overused their accessory breathing muscles and did not use their diaphragm for core stability. Additionally, the increase in the respiratory rate indicates that sympathetic activity and stress increased as well.

This is a perfect storm for pain and decreased postural stability. The result? Lower back pain.

Similar results were found in a study that examined diaphragmatic activity during upper and lower extremity isometric activities with external resistance. Individuals with lower back pain presented with smaller diaphragmatic excursion than pain-free control subjects during the resistance exercises.

Essentially, the subjects with lower back pain were not using the diaphragm to its fullest potential. They were, therefore, more vulnerable to decreased core control and resultant low back pain. Collectively, these results highlight the role of breathing in physical therapy and call for stabilization interventions that involve the diaphragm.

In order to achieve optimal core stabilization, the diaphragm must be simultaneously involved in respiration and postural stability. Individuals who are limited in their ability to contract the diaphragm for stabilization have a higher risk of developing back pain.

Breathing dysfunction restricts mobility

Inefficient breathing patterns are often closely linked to mobility restrictions. If a patient presents a mobility limitation anywhere from the neck to the pelvis, we should consider the possibility of breathing dysfunction.

Many of our patients who present with head, neck, and shoulder pain are likely to suffer from accessory respiratory muscle overuse. We need to retrain breathing in physical therapy in order to decrease accessory muscle overload and increase activation of the diaphragm.

Inefficient breathing patterns may also restrict the rib cage or thoracic spine, which will limit shoulder range of motion. Let's look at the shoulder mobility component of the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) as an example. If dysfunctional breathing patterns have resulted in decreased thoracic spine extension, shoulder mobility will be negatively influenced. Additionally, rib cage restrictions can affect our ability to breathe deeply and will also limit shoulder range of motion.

General flexibility is also influenced by the way we breathe. In order to improve a patient's range of motion and/or flexibility, we may need to calm the nervous system down with breathing in physical therapy. The parasympathetic nervous system will allow our muscles to relax, whereas the sympathetic nervous system causes them to contract. By teaching patients how to slow down their breathing, prolong exhalation, and breathe through their diaphragm, we can increase flexibility.

Breathing determines movement patterns

In order to achieve optimal movement patterns, we need a stable core from which our muscles can generate movement. Lumbar and pelvic stability depends on coordination between the diaphragm, pelvic floor, and transverse abdominis. These muscles activate prior to purposeful movements in order to establish a stable base. This allows for optimal load transference along the entire kinetic chain and minimizes stress on passive structures, such as ligaments, joint capsules, and joint surfaces.

Failure to coordinate the core stabilizers with the regulation of intra-abdominal pressure makes it difficult to efficiently transfer force from the trunk to the extremities. If we can't properly activate the diaphragm during a simple activity, like an active straight leg raise, then we are certainly not recruiting it properly when kicking a soccer ball or performing a squat. This impairs both our core stability and the resultant movement patterns. If we send our patients back to sports or complex activities without having assessed and treated their breathing in physical therapy, then we have left them vulnerable to re-injury.

Breathing changes pain perception

People with chronic pain benefit from exercises that induce relaxation. Since deep breathing calms the nervous system, it will help decrease the stress response associated with pain.

Patients with chronic pain may have an up-regulated nervous system in which there is an increase in sympathetic activity. This increases their sensitivity to touch and heightens their perception of pain. Deep breathing will mediate sympathetic arousal and increase pain thresholds. By teaching patients how to diaphragmatically breathe, we can increase parasympathetic activity, thereby inducing relaxation and decreasing the pain response.

Additionally, dysfunctional breathing may predispose individuals to faulty muscular adaptations, resulting in chronic musculoskeletal pain. For example, people who overuse their neck to breathe will be more susceptible to neck pain. Similarly, weakness in the diaphragm and pelvic floor can lead to overuse of compensatory muscles and result in chronic low back pain. By addressing breathing in physical therapy, we can restore muscle balance and decrease pain.

Assessment of breathing patterns

A breathing assessment is an often overlooked component of an orthopedic physical therapy examination. However, breathing is the foundation of stability and normal movement patterns. Therefore, a breathing assessment should be a basic starting point for all orthopedic evaluations.

When assessing breathing, we must first rule out structural problems, such as airway obstructions or a deviated septum. For example, before we correct someone's posture, we should make sure that they are not standing that way due to anatomical obstruction. Treatment of these respiratory health problems is beyond our scope of practice and will require referral to another specialist.

After we clear anatomical obstructions, we can examine the patient's breathing pattern. The easiest way to do this is by having the patient lay supine and place one hand on the stomach and the other on the chest. If the patient is diaphragmatically breathing, you will see more movement through the stomach and less movement in the chest. If the patient is an apical breather, you will see minimal movement through the abdominal wall and excess movement through the upper chest. Also, take note of the rate of breathing. Is the patient breathing slowly or rapidly? Are the inhalations longer than the exhalations?

There are of course more in-depth methods of examining breathing in physical therapy, but many of us are crunched for time in the orthopedic clinic. This is a quick and simple way to key into a patient's breathing pattern.

Re-training breathing in physical therapy

Breathing can be an essential tool in the treatment of musculoskeletal dysfunction. However, like any intervention, breathing re-training should not be done in isolation. Breathing dysfunction may be the cause, or result of, the patient's primary complaint. Therefore we should coordinate mobility and strength interventions with breathing in physical therapy.

When first instructing a patient in diaphragmatic breathing, it is easiest to have them lay supine on a mat or plinth. Have your patient place one hand on the stomach and the other on the chest in order to compare the excursion of both areas. During diaphragmatic breathing, the patient should feel the stomach rise and fall and the lower rib cage should expand laterally. There should be minimal movement through the chest.

As the patient practices diaphragmatic breathing, watch for compensation of spinal extensors (excess lumbar lordosis) as well as overuse of the rectus abdominis. Also, make sure that the patient does not revert to their old patterns by using accessory respiratory muscles of the chest and neck. This can happen as the patient starts to fatigue.

After a patient has mastered simple corrective breathing exercises, proper breathing should be incorporated into functional activities. When patients participate in complex activities, like running, they experience increased demands for stability and respiration. In order to adequately prepare them for this transition, we need to ensure that our patients are able to properly recruit the diaphragm during more complex activities in the clinic.

Continuing education

While many of us can incorporate basic breathing into our treatment programs, there are several established treatment paradigms that utilize more advanced breathing techniques. The best way to learn these techniques is by taking a continuing education course that focuses on the role of breathing in physical therapy.

Here are a few starting points:

- Postural Restoration Institute (PRI) teaches theory, assessment, and treatment techniques that incorporate breathing into orthopedic physical therapy

- Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA) examines the influence of breathing on movement dysfunction

- Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization (DNS) focuses on the role of the nervous system on posture and movement.

Start breathing in physical therapy today

Breathing is the root of all movement. We must therefore respect the role of breathing in physical therapy. By incorporating breathing into our assessment and treatment of patients with musculoskeletal impairments, we can improve outcomes and increase the likelihood of lifelong recovery. Start helping your patients breathe better today and give them the best chance of achieving optimal function.

Wondering which PT setting may be best for you? Take the quiz below to find out.

References

Breathing. Gray Cook. http://graycook.com/?p=1488. Published July 2013.

Bordoni B, Zanier E. Anatomic connections of the diaphragm: influence of respiration on the body system. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013; 6: 281–291.

Boyle K, Olinick J, Lewis Cynthia. The value of blowing up a balloon. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2010 Sep; 5(3): 179–188.

Bradley H, Esformes J. Breathing pattern disorders and functional movement. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014 Feb;9(1):28-39.

Busch V, Magerl W, Kern U, et alThe Effect of Deep and Slow Breathing on Pain Perception, Autonomic Activity, and Mood Processing—An Experimental Study. Pain Med. 2012 Feb;13(2):215-28.

Chapman EB, Hansen-Honeycutt J, Nasypany A, et al. A clinical guide to the assessment and treatment of breathing pattern disorders in the physically active: part 1. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016 Oct; 11(5): 803–809.

Core Stability from the Inside Out. Hans Lindgren DC. http://www.hanslindgren.com/blog/core-stability-from-the-inside-out-reposted/. Published January 10, 2015.

Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization (DNS): According to Kolar, A Developmental Kinesiology Approach. Rehabilitation Prague School. http://www.rehabps.com/VIDEO/DNS_What_Is.html. 2016.

Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization “A”. JeffCubos.com. http://www.jeffcubos.com/2011/01/17/dynamic-neuromuscular-stabilization-a/. January 17, 2011.

Frank C, Kobesova A, Kolar P. Dynamic neuromuscular stabilization and sports rehabilitation. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013 Feb;8(1):62-73.

Hansen-Honeycutt J, Chapman EB, Nasypany A. A clinical guide to the assessment and treatment of breathing pattern disorders in the physically active: part 2, a case series. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016 Dec;11(6):971-979.

Hodges PW, Gandevia SC. Changes in intra-abdominal pressure during postural and respiratory activation of the human diaphragm. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:967-976.

Hoffman J & Gabel P. Expanding Panjabi’s stability model to express movement: A theoretical model. Med hypotheses. 2013;80(6): 692-697.

Kolar’s Approach to Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization. Standardized Sport and Fitness Handouts: Part 1. Mgr. Michael Truc PT.

Kolar P, Neuwirth J, Sanda J, Suchanek V, Svata Z, Volejnik J, Pivec M. Analysis of Diaphragm Movement during Tidal Breathing and during its Activation while Breath Holding Using MRI Synchronized with Spirometry. Physiol Res. 2009;58(3):383-92.

Kolar P, Sulc J, Kyncl M, et al. Postural function of the diaphragm in persons with and without chronic low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012 Apr;42(4):352-62.

Kolar P, Sulc J, Kyncl M, Sanda J, Neuwirth J, Bokarius AV, Kriz J, Kobesova A. Stabilizing function of the diaphragm: dynamic MRI and synchronized spirometric assessment. J Applied Physiol Aug 2010.

Lederman E. The myth of core stability. J of Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14(1): 84-98.

Lee, BK. Effects of the combined PNF and deep breathing exercises on the ROM and the VAS score of a frozen shoulder patient: Single case study. J Exerc Rehabil. 2015 Oct; 11(5): 276–281.

Master Your Breathing to Perform Better. EXOS. http://www.coreperformance.com/knowledge/wellness/master-your-breathing-to-perform-better.html. Originally published June 8, 2013. Updated August 17, 2015.

Performance Breathing: A Primer. EXOS. https://www.performbetter.com/webapp/wcs/stores/servlet/PBOnePieceView?storeId=10151&catalogId=10751&pagename=593. Published August 2015.

Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW. Disorders of breathing and continence have a stronger association with back pain than obesity and physical activity. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52(1):11-6.

Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW. Do incontinence, breathing difficulties, and gastrointestinal symptoms increase the risk of future back pain? J Pain. 2009 Aug;10(8):876-86.

Yadav G, Mutha PK. Deep Breathing Practice Facilitates Retention of Newly Learned Motor Skills. Sci Rep. 2016 Nov 14;6:37069.

Images

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/RJq4NRW62xI/maxresdefault.jpg

https://bebrainfit.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/parasympathetic-sympathetic-nervous-system.png

http://www.thedoctorsofpt.com/single-post/2017/03/17/Low-Back-Pain-and-Core-Strength-Intra-Abdominal-Pressure

http://postfiles10.naver.net/20161009_9/skylight_blu_1476019149466rAyA8_PNG/IAPandposture.png?type=w773